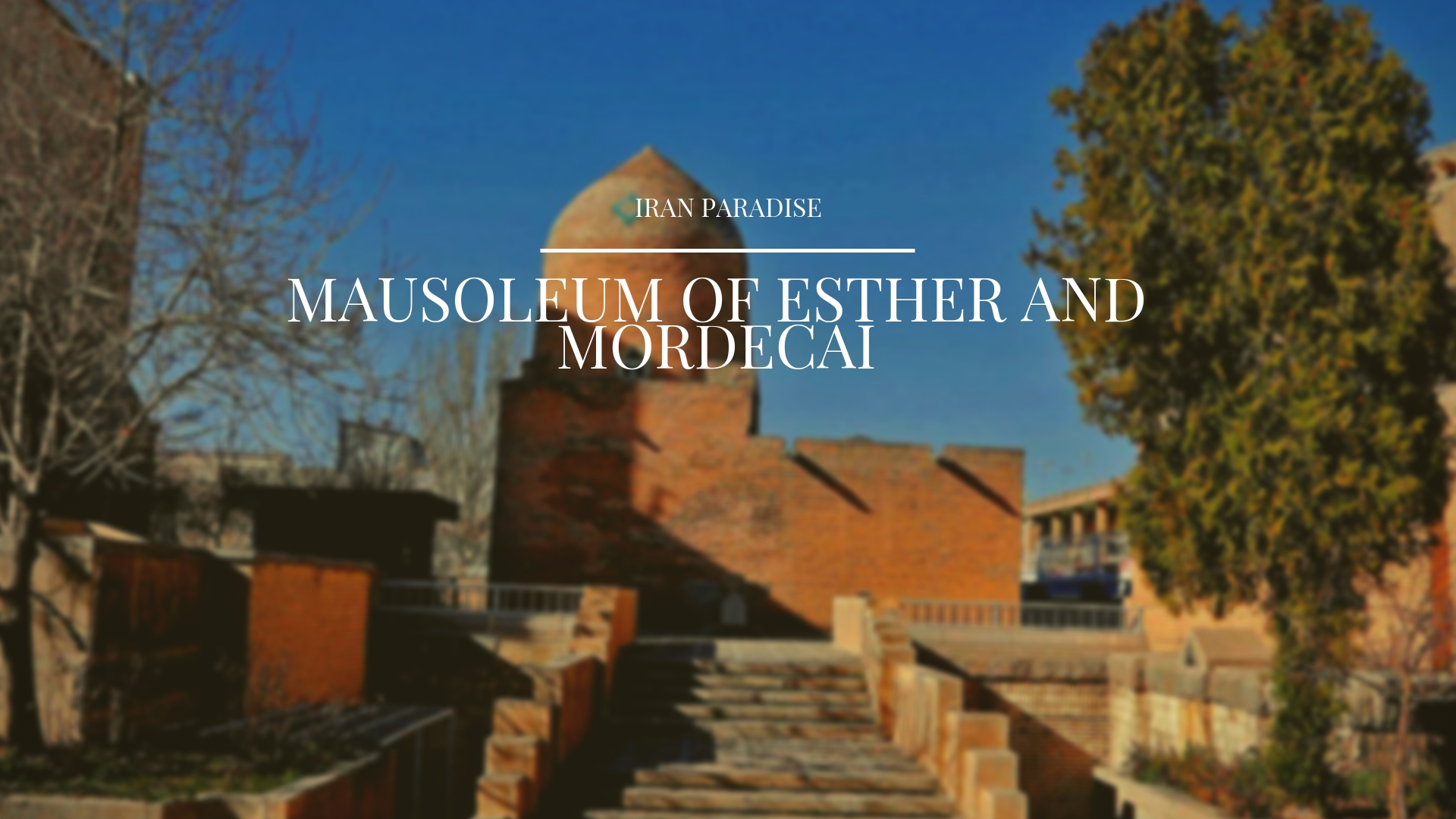

Mausoleum of Esther and Mordecai

Mausoleum of Esther and Mordecai, a Jewish shrine in the city of Hamadān, where, according to Judeo-Persian tradition, Esther and Mordechai are buried. This tradition is not supported by the Jews outside of Persia and does , a Jewish shrine in the city of Hamadān, where, according to Judeo-Persian tradition, Esther and Mordechai are buried. This tradition is not supported by the Jews outside of Persia and does not appear in either Babylonian or Jerusalemite Talmuds. The earliest Jewish source on the tombs is Benjamin of Tudela, who visited Hamadān in the year 1067. According to him, there were 50,000 Jews living in Hamadān, where Esther and Mordechai were buried in front of a synagogue. Šāhīn, the earliest Judeo-Persian source on this tradition, describes the dreams of Esther and Mordechai and their departure to Hamadān, where they died inside the synagogue, first Mordechai, and then Esther, an hour later (Bacher, 1908b, pp. 70-71). Šāhīn’s account is perhaps based on some lost Judeo-Persian sources.

This mausoleum is the most celebrated shrine for Iranian Jews, who venerate it as the burial place of two biblical figures, Esther and Mordechai. According to the Book of Esther in the Old Testament, Esther, the wife of Ahasuerus (probably a transcription of Xerxes, the Achaemenid king of Persia ca. the 4th century BCE) saved the lives of her uncle Mordechai and the entire Jewish community in the Persian Empire from a sinister plot by Haman, one of the king’s courtiers. The Jewish feast of Purim is based on the tale of Esther. Christians and Muslims alike venerate the shrine, which was once situated within the Jewish quarter of Hamadan. The building is attributed to the fourteenth century.

Oriented toward west (Jerusalem), the mausoleum consists of a 12-meter-high domed chamber (5.3 meters per side) with secondary rooms attached to the north and east. According to historical sources, famous rabbis were buried in these rooms.

The building is accessed through a shallow iwan containing a low doorway with a massive granite door, which obliges visitors to bow upon entering. Interior walls are covered with Hebrew inscriptions executed in stone or plaster. In the main hall are two wooden coffins; these are attributed to Esther and Mordechai and carved in intricate geometric patterns and Hebrew inscriptions. While the sarcophagus attributed to Esther is dated 1291 (692 A.H.), the other was made in the second half of the seventeenth century.

In the early 1970s, the shrine was renovated and expanded by the order of the Iranian Jewish Society. The renovation, undertaken by architect Yassi (Elias) Gabby, involved the demolition of surrounding residential buildings and the erection of a modern synagogue.

We have more detailed descriptions by the 19th and 20th century authors. Israel ben Joseph, known as the Second Benjamin, who visited Hamadān in 1850, reported that the tombs, separated from each other by a narrow path, were in a room in a magnificent building located inside the city close to a city walls. According to him, the Jews came here to pray once a month. In the feast of Purim (14th of Adar) they read the Book of Esther and from time to time hit the tombs with the palms of their hands. He estimated the number of the Jews in Hamadān as about 500 families who owned three synagogues. Yehiel Fischel Castelman, a Galician Jew from Safed, visited Hamadān in 1860. He praised the economic situation of the Jews of Hamadān and described the edifice and the tombs as magnificent. He reported that, according to the local Jews, it was “built by Cyrus the son of Esther,” and that the date was written on the top of the dome. He, however, “could not climb to read it.” Jakob Pollak, Nāṣer-al-Dīn Shah’s physician and professor of anatomy in Dār al-Fonūn (1855-60), mentions the tombs as the only national holy place that the Jews of Persia possessed and made pilgrimage to. He said they were situated in the center of the Jewish quarter inside a thirty-foot high domed building. The entrance was through a low and narrow opening and could be shut by a doorlike stone. The first room had a low ceiling and on its walls were engraved the names of the visitors. In a nearby smaller room were two coffins made of oak, set two feet apart, on which were written the last passages of the book of Esther, the names of three physicians who had donated money for the repair of the tombs, and a date corresponding to 1309-10 C.E. Inscriptions on the walls gave the ancestry of Esther and Mordechai. A date corresponding to 1140 C.E. was found in the smaller room. He added that Muslims called the shrine Emāmzāda (q.v.).

Rabbi Menaḥem ha-Levi of Hamadān (d. 1940) mentions an inscription from Isaiah 26:2 on the entrance. According to him, the first room was built 200 years before and under it were buried the physician Yiṣḥaq ben Avraham and an emissary from Hebron. In the center of the room was buried the chief rabbi of Hamadān, Elyahu ben Elʿazar (d. 1865). He also mentions an opening between the two tombs, through which one could descend into a cave used for repairs. He gave the height of the building as 20 m.

The archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld described the place as a simple structure which has been restored several times. The oldest part was the underground tomb-chamber with a small opening in the top of its vault, and two wooden cenotaphs, one of which is of the Mongol period. Herzfeld rejected the tradition relating the tombs to Esther and Mordechai, who he said were buried in Susa. He maintained that Šūšandoḵt, the daughter of the Jewish Exilarch and wife of the Sasanian Yazdegerd I (r. 399-420), was buried in one of the tombs.

Tags:Benjamin, doorlike, Esther, Esther and Mordecai, Hamadān, Herzfeld, Iranian Jewish Society, Mausoleum, Mausoleum of Esther and Mordecai, Mordecai, Mordechai, sarcophagus, Sasanian, Susa, Yassi, Yazdegerd, Yiṣḥaq ben Avraham

kjГёp prozac og viagra her 50 mg viagra vvbfurd – viagra for sale in florida

Viagra Sildenafil 50mg

Buy Propecia For Women

buy real cialis online

finasteride amazon

where to buy zithromax online cheap

Cialis Generico A Basso Costo canada oil kamagra chewable Buy Cheap Viagra Online Usa

Your web site is very much worthy of a bookmark. Thank you for the good post!

ivermectin 1 cream generic stromectol 3 mg price

[url=http://buycialikonline.com]buy cialis cheap[/url] Cialis Se Necesita Receta Medica

Free spins are a popular bonus option offered by online casinos. Casinos award free spins for a variety of reasons. Free spins are a way to attract new customers to their platform or as a thank-you to higher volume players. Casinos might also offer free spins in order to promote one of their newest slot machines. In addition to that, iOS users may even download a separate app. The official All Slots Casino mobile app can be found in the AppStore. It is free to download and has an overall rating of 4.5. Remember that you should have at least iOS 10 installed for the app to function properly. Still, Android users will have to enter the site from a browser, as there is no app available for this type of devices. However, a future Android app development is not out of the question. Some online casinos go heavy on slots and skimp on table games. All Slots isn’t like this, though, and offers over 50 titles. It features everything from multi-wheel roulette to a blackjack variation based on legendary footballer Vinnie Jones. You can see a sample of the All Slots table games below:

http://www.paperbooks.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=32568

Another of the most famous casinos, BetMGM Casino, offers players the most extensive number of games. The operator constantly adds new slots on a weekly basis, so there’s always a new slot or two to try. The two newest Dragon Link™ bank mates, Dragon Link Peacock Princess™ and Spring Festival™ bring brilliant and colorful Asian-themed experiences with big symbols to the Dragon Link family, a player favorite in the Australian gaming market. You can enter the Dragon with 1c, 2c, 5c, 10c, $1 and $2 denominations, making this a truely entertaining experience. Snoop Dogg – The Joker’s Wild Slot Game Join our newsletter! First of Five Awards, New Positions Target Primary Care and Mental Health Since your last visit, you will notice many changes to our gaming floor. Plexiglas, separation risers are in place to promote social distancing. We have implemented enhanced cleaning and meet all standardized protocols. The Slot Team will execute these enhanced cleaning protocols by routinely disinfecting each gaming machine and chair. To further promote our health and safety guidelines social distancing markers and proper hygiene signage has been placed across the casino property. Over a dozen highly visible hand sanitation stations are available throughout the gaming floor.

I am an investor of gate io, I have consulted a lot of information, I hope to upgrade my investment strategy with a new model. Your article creation ideas have given me a lot of inspiration, but I still have some doubts. I wonder if you can help me? Thanks.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

5 Killer Quora Answers On Affordable Link Building Services Affordable Link building

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

黃金守護神(特殊大賞燈);

カスもカジノ

リーチ演出が多彩で、どのタイミングで大当たりが来るかワクワクします。

P 北斗の拳 暴凶星

https://rioace.jahromblog.com/post-268/

シンプルなルールで、初心者でもすぐに楽しめます。気軽に挑戦できるのが良いです。

CR戦国乙女〜花〜

[url=https://www.ja-securities.jp/games/id1998]

パチスロ バキ モード[/url]

甲賀忍法帖Ⅲ

戦律のストラタス

沖ドキ!トロピカル

L 大工の源さん 超夢源

[url=https://www.ja-securities.jp/games/id1624]

バジリスクやめ時[/url]

真モグモグ風林火山2

八代將軍戰神版

P 北斗の拳 暴凶星

シティーハンター

[url=https://www.clubgaminator-slots.com/article/73.html]

カジノジャンボリー 評判[/url]

CR牙狼GOLDSTORM翔 Ver.319

HEY!エリートサラリーマン鏡

P 新世紀エヴァンゲリオン ~未来への咆哮~ SPECIAL EDITION

CR牙狼魔戒ノ花

https://www.k8.army/Articles/1678.html

定期的に新しいイベントがあり、飽きずに楽しめます。新しい体験が待っています。

CR牙狼 魔戒ノ花XX

https://idtc.jp/tags/p-%E9%A0%AD%E6%96%87%E5%AD%97d-non%E2%80%90stop-3000-edition

定期的に新しいイベントがあり、飽きずに楽しめます。新しい体験が待っています。

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://accounts.binance.info/en-IN/register?ref=UM6SMJM3

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!