The Persian Qanat

Qanat is a symbol of civilization, tradition and culture in desert regions with arid climate and an outstanding example of using architectural complicated systems in Iran. In fact, Qanat is a tunnel-like channel underground which collects water from a main water source naming “mother well” in order to conduct water along tunnels and finally enable settlement and agriculture. The place where the water of Qanat exits from the surface is named Mazhar. The eleven qanats representing this system include rest areas for workers, water reservoirs and watermills. The traditional communal management system still in place allows equitable and sustainable water sharing and distribution. The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.

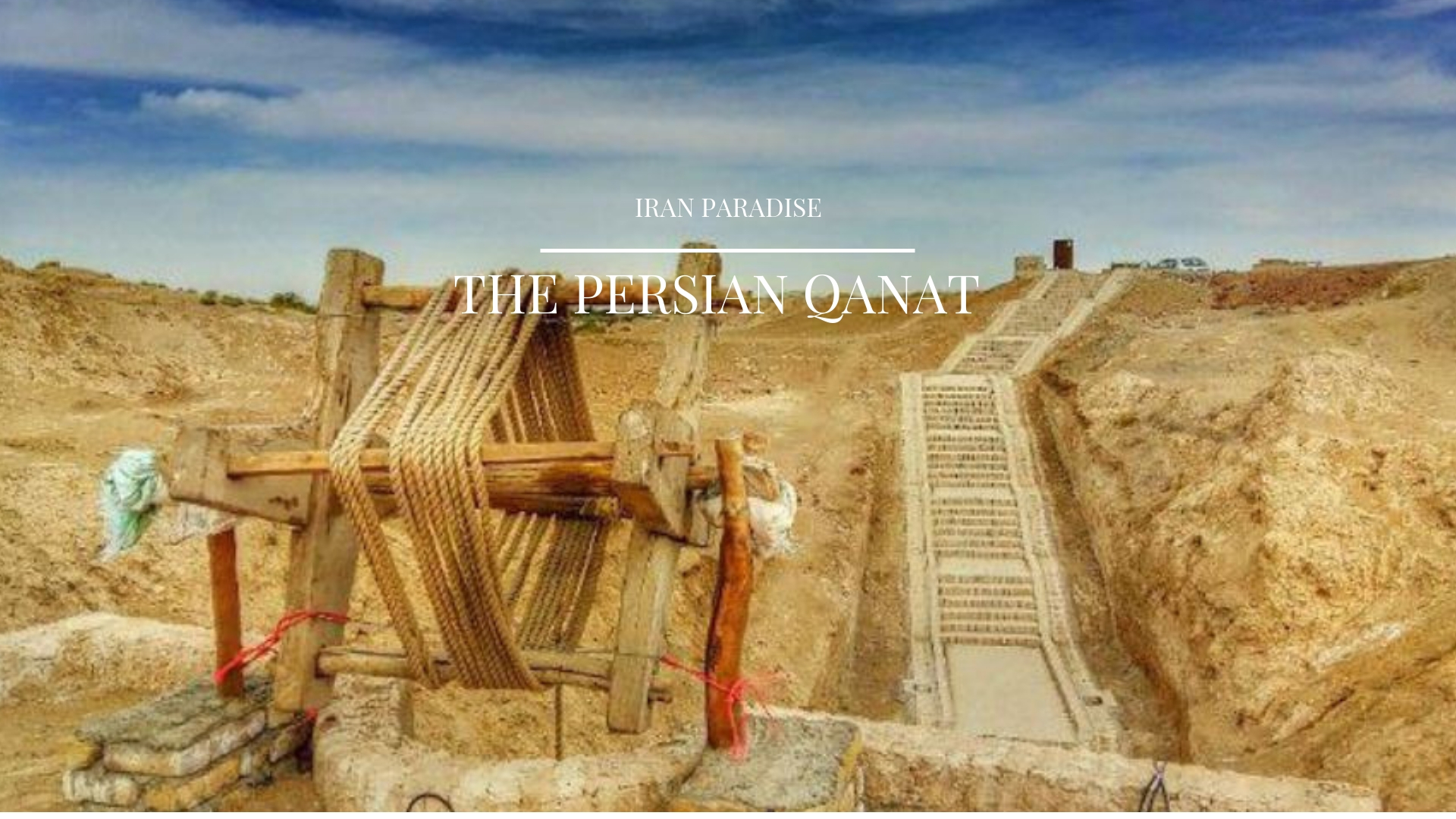

Qanats, are 3,000-year-old marvels of engineering in deserts, many of which are still in use throughout Iran. Beginning in the Iron Age, surveyors—having found an elevated source of water, usually at the head of a former river valley or even in a cave lake—would cut long, sloping tunnels from the water source to where it was needed. The orderly holes still visible above ground are air shafts, bored to release dust and provide oxygen to the workers who dug the qanats by hand, sometimes as far as forty miles. The tunnels eventually open at ground level to form vivid oases.

The traditional communal management system still in place allows equitable and sustainable water sharing and distribution. The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate. Each qanat comprises an almost horizontal tunnel collecting water from an underground water source, usually an alluvial fan, into which a mother well is sunk to the appropriate level of the aquifer. Well shafts are sunk at regular intervals along the route of the tunnel to enable removal of spoil and allow ventilation. These appear as craters from above, following the line of the qanat from water source to agricultural settlement.

Astonishingly, the structure of this aqueduct has caused its name to be registered by the Cultural Heritage Organization in 2000 with the number 2963 in the national list of Iran and at the Istanbul Summit on July 24, 1959 in the list of works registered at UNESCO. Persian Qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate. The Iranians rip the foothills in search of water, and when they find any, by means of Qanats they transfer this water to a distance of 50 or 60 kilometers or sometimes further downstream.

Besides the Qanats providing necessary drinking water, it also helps cooling down indoor temperatures. In Yazd, an Iranian city where summers can be extremely hot, the qanat is very important. The combination of a qanat and an Iranian wind catcher (Badgir), creates a cooling effect. The warm incoming air comes through the shaft and transforms into cool air by the qanat’s cold water. This ancient method of air conditioning is still widely used, especially in hot cities like Yazd.

Constructing qanats was a painstaking task, made even more so by the need for great precision. The angle of the tunnel’s slope had to be steep enough to allow the water to flow freely without stagnating—but too steep and the water would flow with enough force to speed erosion and collapse the tunnel. Although difficult work—even after completion, qanats require yearly maintenance—the irrigation tunnels allowed agriculture to bloom in the arid desert. The technology spread, through Silk Road trade and Muslim conquest, and qanats can be found as far as Morocco and Spain.

The qanats were also a great way to maintain beautiful oasis-like Persian gardens. These gardens are filled with flowers, trees, water fountains and waterways. All of them are fully arranged in harmony and symmetry to reflect the Zoroastrian adoration of nature and its elements.

The water is transported along underground tunnels, so-called koshkan, by means of gravity due to the gentle slope of the tunnel to the exit, from where it is distributed by channels to the agricultural land of the shareholders. The levels, gradient and length of the qanat are calculated by traditional methods requiring the skills of experienced qanat workers and have been handed down over centuries. Many qanats have sub branches and water access corridors for maintenance purposes, as well as dependent structures including rest areas for the qanat workers, public and private bath, reservoirs and watermills.

Tags:Badgir, cooling down, Cultural, Cultural Heritage, Cultural Heritage Organization, cultural traditions, drinking water, heritage, indoor temperatures, Iranians rip, Organization, Persian, Persian gardens, qanat, raditional methods, Silk Road, The Persian Qanat, underground tunnels, UNESCO, watermills, Yazd, Zoroastrian